A Drawing by Edwin Dickinson. The Studio at 46 Pearl Street

|

| Studio, 46 Pearl Street, 1926 |

Earlier my father lived year round for four years in studios at Days Lumberyard. He enlisted in the U. S. Navy in 1917 and was proud his name is inscribed on the World War I monument in front of Town Hall. Discharged in 1919 he visited his family, and in December went on a long delayed trip to Europe, spending most of six months in Paris. On his return to Provincetown he was settling into the Pearl Street studio by September 1920.

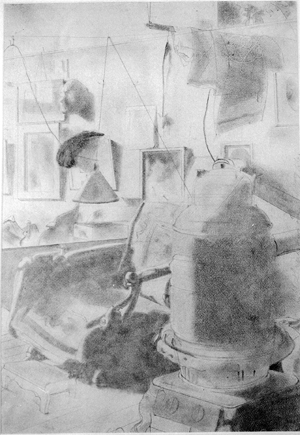

This drawing of his studio/home has an expansiveness which makes it feel almost like a full room. In fact all that he shows is the southeast corner, which is made bright by the sun coming in from the great north light out of sight at the upper left.

He must have been drawing on a brilliant day, for the shadows are strong all along the east wall, on the pictures and objects, the chair and stove. The tops of the carved arms of the sagging old easy chair are strongly highlighted as is its back. To the right of the chair a veritable pool of shadow connects it to the stove, also strongly lit and shadowed. Another “pool of black” brings us to the lower right corner of the drawing.

The chair and stove occupy such a large amount of space that very little of the bare floor is visible. The stove seems at first glance exceptionally tall, but a closer look reveals that its top is actually a large kettle, its lid’s knob and the spout drawn with almost loving care. This kettle was always on the stove to provide hot water. The stove pipe angles its way to the wall and above it is suspended a bar on which towels are drying. This arrangement was extremely practical, but I think my father always had a bar with hanging fabrics in his studios. He loved drapery, loved to paint it, and liked pointing out that it was ‘amenable’, as he would say, to being arranged however one liked and then would stay put.

There are at least eight pictures on the wall, hung according to no discernible system. Each is tipped forward slightly differently so the shadows behind them vary in size and complexity, thus enlivening the entire wall. One is unframed, only matted, and so pressed flat against the wall, but its lower right corner has become unstuck so it casts yet another kind of shadow. The drawing at the upper left has slipped in its frame, and being nearest the north light, has picked up in its glass a reflection of the north window. One drawing has a large feather plume draped over it. The only identifiable picture is above the chair. It is a portrait of a Venetian lady (ca. 1905) by Charles W. Hawthorne who had a studio next door to my father’s, at 48 Pearl Street. Hawthorne offered it to my father, (Hawthorne’s former student and assistant), if he would give in exchange his painting Couple Dancing on a Table (1913) which Hawthorne particularly admired.

The strong shape of the hanging lamp, with the taut lines which suspend it, though not the actual center of the drawing, in fact stabilizes the entire composition of casually arranged belongings.

Father’s studios were always filled with a tremendous variety of artifacts. Broken china, drapes, and furniture from his grandparents’ house mingled with things that in some way attracted him from the town dump. One of his finds, a single old boot, he placed in a large glass lantern box and painted it into his ˆTwo Figures II (1922-1924), now hanging in the Metropolitan. The old bent harpoon and the death mask of Beethoven seen here were among the things he kept all of his life.

Though others might consider his studios cluttered and crowded, for my father every object had an association which was for him nourishing, even inspiring.

The decade of the ‘20s was strikingly productive for my father. It was at 46 Pearl Street that he painted three major and very large paintings which were to make his early reputation. Each of these paintings took many “sittings,” as he liked to say. He considered that the number of three to four hour sessions of actual painting (rather than the number of years during which he painted) gave the most accurate count of the time required to produce the final picture.

On October 11, 1920, his 29th birthday, he began a large composition, An Anniversary (1920-1921, measuring 6 x 5 feet. Floyd Clymer was one of the friends who posed for it. It was followed by The Cello Player (1924-1926), 5 x 4 feet, which occupied 290 sittings. The Fossil Hunters (1926-1928). at just over 8 x 6 feet; became a prize winner and created a sensation when shown in the prestigious Carnegie International exhibition in 1928. My father was unusual among painters of the ‘20s in producing such large works and these three paintings were to make his name for years to come.

In the early ‘20s he already had a reputation as a daring and brilliant painter and in about 1924, young Janice and Jack Tworkov hitchhiked from New York to Provincetown to meet him. The Tworkovs were sister and brother, newly arrived from Poland. Both became noted painters, both left their mark on Provincetown and they and my father became life-long friends.

At Pearl Street in the ‘20s, my father also painted portraits of good friends such as Janice Tworkov (Biala); his old friend Barby Brown (Malicoat) who posed for The Fossil Hunters; Elsbeth Miller (daughter of painter Richard E. Miller), with whom he used to go ice skating on Shank Painter Pond; and Pat Foley, a Hawthorne student, during their courtship in 1927. When he met Pat he was already a good friend of her eldest sister Edith Foley (Shay) who was one of the ‘Smooleys.” The Smooleys were vibrant figures in the social world of Provincetown’s artists and writers. Four friends, Edie Foley, Katie Smith (Dos Passos), her brother Bill Smith, and Stella Roof, lived in a house bought from Mary Heaton Vorse and combined their last names to make the group name.

My father’s parents and siblings called him Edwin, but everyone in Provincetown knew him as “Dick” and Dick he remained for the rest of his life. In the fall of 1928 he hurried to finish The Fossil Hunters, so he and Pat could be married in New York on October 31st. Dick and Pat spent the winter in his father’s cottage on Cayuga Lake in Sheldrake, New York, and returned to Provincetown in late April 1929. They lived first in the little mansard-roofed house beside the studio and later in the studio itself. The studio (today still much as it was) had basic plumbing and a sleeping loft. Before his marriage Dick’s sister Antoinette, known as Tibi, lived many years in Provincetown, keeping house for her brother and Cy Young moved the little mansard house to Pearl Street for her to live in. Her brother’s wide circle of friends became hers as well. As late as the 1960s I remember Provincetown friends calling out to my father, “And how’s Tibi?”

Tibi so loved Provincetown and 46 Pearl Street that in 1931 she came from Sheldrake, New York to have her wedding there. With her father officiating, she and Henry Van Sickle were married in the studio on November 12th. I was six months old and slept through it all in a basket set below the north light.

My father was an extremely gregarious and sociable man. He loved parties and evenings at the Frederick Waughs listening to music. He loved walking across the dunes to the back shore where he befriended the men of the Life Saving Service, who walked the ocean beach day and night watching for wrecked ships. He and painter Henry Sutter liked to walk to the ocean beach and stamp out in immense letters such names as Beethoven or Bach, thus paying a kind of homage.

Henry and Dick were also practical jokers and at Days Lumberyard in the winter of 1915-1916, they painted portraits of each other on a single canvas and entered it in an Art Association Show under the name of Dimitri Vasclav.

Dick and Caro Campbell were long-time close friends and they might go to chamber music concerts or the movies. He was an ardent chess player, including blindfold chess. He and Floyd Clymer or Dick Parmenter sailed as often as they could. He and Tibi, and later Pat, often entertained in the studio over tea or supper and they liked to dance. He and artist Florida Duncan were particular friends. She died early in 1931, the year I was born, and in her memory I was named Helen Florida.

My father always worked by stable natural light coming only from the north; never by artificial light or the glaring south light from the studio’s door and window. They were kept covered when he was working. Born in 1891, though a child of the 19th century, he became enthralled when he went to New York to art school in 1910, by all he could see and learn of early modern art abroad. It was typical of him to choose to draw only a small section of his studio, and at an oblique angle. He delineated forms with both hard pencil edges and soft boundaries, as with the shadow on the back of the stove or the harpoon on the wall. He was ready to render objects incompletely, as with the left hand picture on the wall and the stove pipe and the picture above it. The drawing has a poised equilibrium between the fully drawn and the things which continue beyond its boundaries; especially at the top where the wall carries a horizontal strip of moulding but seems to rise beyond it almost infinitely far. He appears to render every item with much the same surface whether it be metal, cloth, or glass. He had an uncanny ability to render the most homely, even decrepit objects, in a way that gives them a kind of grandeur. I think the effect of the drawing is that of a fascinating place. One does not think first of its poverty. There is no bravura to this drawing. Its effect is that of an unusually large still life.

My father died in 1978 after 50 years as an artist. His drawing of 46 Pearl Street is so distinctive and original that it cannot be mistaken for the work of any other artist. To those who knew him, the man who lived here is instantly recognizable. To those who know his work, the drawing is as individual to him as his signature.