Observations on Composition

Helen Dickinson and I were married in June 1953. She had just graduated from Oberlin College with a degree in Art History and had been hired as a staff docent at the Yale At Gallery while I finished up my studies as a theatre designer at the Yale School of Drama. I had known very little about Edwin Dickinson’s work.

The first fifteen years of our marriage were to be very good ones for my father-in-law; a one artist national touring exhibition to twelve cities organized by the Museum of Modern Art, a major retrospective of his work occupying all three floors of the Whitney Museum of American Art and participation in Paintings by Members, 1968, of the American Academy and National Institute of Arts and Letters at the time of his election to membership in the American Academy. In addition to these, his work was included in over fifty other exhibitions.

|

| Carrousel Bridge, 1952 |

|

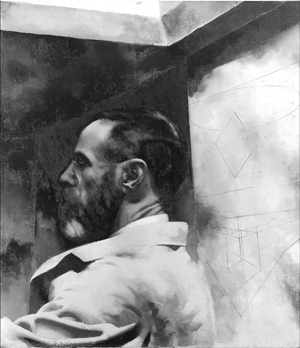

| Self Portrait, 1949 |

Over the sixty years of our marriage and most poignantly during the past twenty years during which my wife has worked on the data and images for this Catalogue Raisonné I have learned more about the several ways that my father-in-law approached his work. Here are several observations about different factors affecting a painting’s composition.

A large number of his paintings were done in one sitting. These he called premier coups, literally ‘first strikes,’ paintings produced over several hours painted outdoors, en plein air. Others which may have been started as subjects for premier coups were developed further with one or more additional sittings. Carrousel Bridge, 1952, is one such. It was painted from a station point near the level of the Seine looking past the Pont du Carrousel with part of the Musée du Louvre in the background. Here the composition was dictated, to use his words by “the site (or sight) taken as seen.”

Paintings which include a live model require the posing of the subject. Self portraits are a very special instance and the posing in these cases is often conceptual involving the uses of mirrors. The composition of the Self Portrait, 1949, places Dickinson’s head in the center of the painting turned away from the viewer and a conventional perspective drawing of a rectangular solid to the right of the center, the drawing itself rendered in perspective. That and the unusual lighting of the subject by a skylight directly overhead reflects both his interest in perspective and his uses of unconventional compositions.

|

| South Wellfleet Inn, 1939 |

A drawing which Dickinson made of the South Wellfleet Inn in 1939 just before that hotel burned is used as the subject of the painting, South Wellfleet Inn, 1955–60. This painting is large and one in which Dickinson composed the subject matter to make his point rather than “the site taken as seen.” In the painting, the view of the building is repeated several times as the images cascading in ever smaller copies to the bottom of the frame. It is a graphic contradiction using two different indicators of depth; an apparent diminution in size indicating depth in contrast to overlapping. It is a graphic contradiction using two different indicators of depth; an apparent diminution in size indicating depth in contrast to overlapping.

We know that objects appear smaller when they are spatially further away from us in nature, railroad tracks and lines of telephone poles appear to converge at a distance. Linear perspective simulates this phenomenon by reducing the size of distant objects.

|

| South Wellfleet Inn, 1955–60 |

The overlapping of one copy of the drawing over another shows us that the smallest of these little drawings must be on top, it overlaps its neighbor. If the same view were not repeated on each of these overlapping drawings or if they were all blank pieces of paper, there would be no apparent contradiction. The confusion arises because each is of the same image. Dickinson seems to be playing with graphic indications of depth.

This was the last of Dickinson’s large paintings. The composition is not from “the sight taken as seen.” It is a construction illustrating a graphic contradiction. It was a work which he mentioned time and again as one that he wished he could have completed. He said that it was different from what he had done previously. It was conceptually based.

Robert Baldwin

Oberlin, Ohio

Summer 2013